#332: Andrea Freeman - Here's the Real Story Behind What's On Your Plate

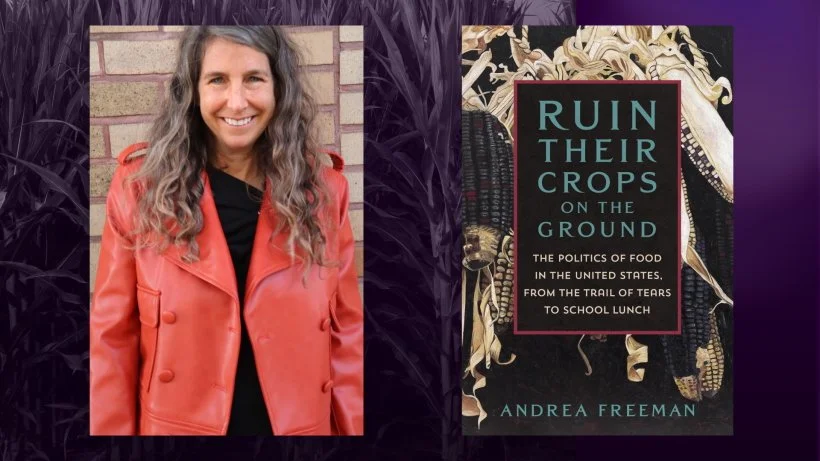

Rip sits down with Andrea Freeman, James Beard Award-winning author of Ruin Their Crops on the Ground. Drawing on more than 20 years of research, Andrea unpacks how food, race, and class have shaped America’s food system, exploring the historical roots of inequality that still influence what ends up on our plates today.

Their conversation takes listeners on a journey from the Trail of Tears to contemporary food policies, revealing how government decisions and corporate interests have systematically marginalized communities, perpetuating cycles of poor health and limited access to nutritious food. Andrea’s insights illuminate the ways in which food systems have been—and continue to be—tools of oppression, while also showing how understanding this history empowers us to advocate for meaningful change.

Rob and Andrea dive into key topics including:

The politics of food and its intersections with race and class

Food deserts, systemic barriers, and ongoing food justice challenge

The historical impact of school lunch programs and agricultural subsidies

How corporate influence shapes dietary guidelines and marketing

The lasting effects of colonial-era food policies on modern diets

Andrea also emphasizes the power of advocacy, inspiring listeners to see food not just as sustenance, but as a reflection of cultural identity and social justice. She encourages critical thinking about the choices available to consumers and how we can support policies that prioritize health and equity over profit.

Episode Resources

Watch the episode on YouTube: https://youtu.be/xVfmEuE1fbE

Order her book, Ruin Their Crops on the Ground

Listen to an NPR interview with Andrea about her book

We hope to see YOU at one of our 2026 Live Events! https://plantstrong.com/pages/events

To stock up on the best-tasting, most convenient, 100% PLANTSTRONG foods, check out all of our PLANTSTRONG products: https://plantstrong.com/

Give us a like on the PLANTSTRONG Facebook Page and check out what being PLANSTRONG is all about. We always keep it stocked full of new content and updates, tips for healthy living, and delicious recipes, and you can even catch me LIVE on there!

We’ve also got an Instagram! Check us out and share your favorite PLANTSTRONG products and why you love it! Don’t forget to tag us using #goplantstrong 🌱💪

Episode Transcript via AI Transcription Service

I'm Rip Esselstyn, and you're listening to the Plant Strong Podcast.

[0:05] The food on your plate tells a very important story, and understanding it can be very empowering. In this eye-opening episode, I sit down with Andrea Freeman. She is the author of the James Beard Award-winning book, Ruin Their Crops on the Ground, to uncover exactly how food, race, and class have shaped America and how understanding this history can help us build a fairer, more just food system. This conversation will influence the way you see your food and inspire you to think about the impact that we all can have. We'll meet Andrea right after these words from Plant Strong.

[0:55] Today, we are going to dive into a topic that's as important as it is eye-opening, how the politics of food have shaped our country and our communities. My guest today is Andrea Freeman. She is the author of the James Beard Award-winning book, Ruin Their Crops on the Ground. Andrea has spent over 20 years researching how food systems have been used as tools of control, and she's here to help us understand the intersections of food, racism, and classism that have existed, well, since our country was first founded. This episode is a deep, fascinating look at history, policy, and the ongoing fight for food justice. And it's also a call for each of us to use the compassion and power that we

[1:48] all have to push for change. Please welcome Andrea Freeman. Andrea Freeman I want to welcome you to the Plant Strong podcast thank you i'm very excited to be here, yeah i'm excited to have you where where am i talking to you from today i am in the city of los angeles.

[2:10] Los Angeles. Yes. Wow. How long have you been in L.A.? About two years now. Yeah. I moved here from Hawaii. I was there for 10 years before this. Yeah. Where in Hawaii? Oahu. So Honolulu, Kailua, different parts of the island. Mm-hmm. Well, do you miss it? Some things about it and others not. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, I bet. I bet. Well, I've been to Hawaii a bunch and it's great, but I've never lived there for more than, I think, two weeks at a time. Yeah, it's an absolutely stunning place to visit. And it's a beautiful and challenging place to live. Yeah yeah uh well we're not here to talk about hawaii no we we are here to talk about a very important piece of work that that you've written uh this is it right here if everybody can see it it's called Ruin Their Crops on the Ground - The Politics of Food in the United States from the Trail of Tears to School Lunch and it is, it's very upsetting. I find incredibly upsetting. I mean, I imagine it was probably.

[3:37] I would imagine difficult to write this book, but at the same time, so important for people to understand what has gone on historically with our food system and how it has kind of created racism and classism as you talk about. But before we dive in, Where were you and what were you doing when you decided that,

The Politics of Food

[3:59] you know what, this is a book that I want to tackle? Yeah. So I started thinking about food and racism when I was in law school and I took a class called The Suburbs, which was cross-listed between law and architecture. And I decided I wanted to write a paper about fast food. And I called that paper Fast Food Oppression Through Poor Nutrition. And that is when the first time I started thinking about the intersections between food and racism. And then I was hooked.

[4:40] And so over the next 20 years, I just explored a lot of different aspects of that. And I was really focused on how corporations and the government partner together to create these, as you said, food systems and conditions where there are really stark health disparities between racialized groups. And then I started thinking about, well, what's the history of this? And that's where I started going earlier and thinking even before the United States became a country, how food had been used as a tool of oppression and subordination throughout history. And once I had all of that, I said, you know what, I think this would be, this is book material. Like this is not something I want to keep to law review journals and the small sort of legal academic community that I'm part of. This is something that I want to share with the rest of the world. Yeah, well, and it's a very uncomfortable truth that you bring out. And so it's something that I don't see people, you know.

[6:02] Swarming to like really want to know the history, unfortunately, but I think it is paramount that we understand the history and why we are where we are today. And so I can't even tell you how much I applaud you for what you've created here and the amount of research that you put into this. Can you let us know how much time did you put in researching for this book? Yes, this is really about 20 years of research. So all the different topics, because you see the range of topics in the book. And yeah, some of it reflects that early work that I did. And then I was still working and researching pretty much like to the point where the editor said no more. Wow. Yeah. And when did it officially come out? That was last summer. So not just like 2024, July. Right. Yeah. Right. Yeah. Well, wonderful. Thanks. Well, what I would like to do, if you'll indulge me, is I think...

[7:13] What to me would make sense, can we kind of go through chapter by chapter? We'll start with chapter one, which is kind of weapons of health destruction. Yeah. Not mass destruction, but health destruction, which actually is mass destruction, isn't it? It's just a little more subtle than we usually think about it. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. And so let's start there. Um you know you know your your subtitle is the politics of food in the united states from the trail of tears to school lunch and why why is it trail of tears i mean is is that did that happen because i i don't know did that happen before 1779 when washington basically said ruin their crops on the ground yeah so it was after but part of that whole strategy okay yeah because that was when andrew jackson became president and then started this real exile across the country so the seeds were planted if if you will with washington's order which is where the title comes from,

Trail of Tears and Food Control

[8:23] he said, ruin their crops in the ground and stop them planting more. And so that was to say, the way we're going to steal this land is by making sure that people living there have nothing to eat.

[8:38] So he ordered his troops to destroy all the land. And, you know, we have massive killing of Buffalo and basically a very focused intent to starve people out. And did the Native Americans, were they not able to put up a fight? Did they just not have weapons? Did they, I mean. Oh, there was a lot of fighting. Yeah. A lot of fighting and resistance. But at the end of the day, if you have no food, you just, you can't survive. Right. And so then there was this push. You, if you go somewhere else along the Trail of Tears and, you know, walk across the country, there's land there and you'll be able to get food from that land and also the promise of rations. Right. And then these rations given by the United States become highly problematic for centuries, like forever. Right. Because they're full of really non nutritious, often rotten and spoiled food that then are causing death and illness. Yeah.

[9:54] And also they start using rations as a kind of political weapon. So it's also, well, if you don't turn your kids over to the federal Indian boarding schools, then your rations are cut off. If you don't have a family system, the way we have them, no more rations. Right. It's used for everything. So yeah so basically this was their way of coercing um these children to go to these, boarding schools right yeah at least they would be fed there but then the food they're fed is not the food that they're used to and then that you know causes a whole other thing because we have this other trend that we still have of trying to americanize people through food, right and that's a that's a whole nother chapter that's true there's overlap yeah right um.

[11:00] Now, tell me this. So, you know, Washington and Jackson basically ruined their crops on the ground, trail of tears. And then so were the were the Native Americans then basically using buffalo? Were they eating buffalo in order to survive? Because at some point in your book, and I'm getting it kind of the chronologically mixed up. But I know that like General Dodge gave this, basically said, kill every buffalo that you can because every dead buffalo is an Indian gone. I mean, that is that just makes my heart just. Yeah, it's devastating. And it was very devastating for the indigenous communities that relied on buffalo, not just for food, but as as culturally, socially, you know, it wasn't just. You know, animals were integrated into the culture and society.

Survival and Revolution

[11:59] Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Okay. So let's talk about, I mean, so that, that, that was very, very, very, very quick, but let's move into now chapter two, which is surviving, survival pending revolution.

[12:18] And here we kind of move move on from kind of Native Americans to, I guess you'd call enslaved people and and and black people. And you basically from slavery to emancipation. So tell me how were how are the black people's diets controlled before and after slavery? Yeah. So, I mean, that's a complex question, of course, and it does have a whole chapter there. But enslavers did very carefully calculate how much food to give enslaved people and varied it according to what work they were doing, what age they were, what gender they were.

[13:08] You know, it was designed to fuel people to work, but to keep them weak so they wouldn't be rebelling, right? Right. Didn't work, of course, but so that would be passed around in pamphlets between enslavers.

[13:29] And of course, they wanted to just use the minimum of their own resources, but still keep people alive. Right. But then what we see is once there is emancipation, there was not much thought given into how people would survive once they were freed. So you had a lot of people just not having any resources, not having food, the creation of the Freedmen's Bureau, which did give out some rationing again to people.

[14:05] But then they quickly kind of gave up on that policy and we see you know something that's echoed today the idea of entitlement and people should just get their own food and you know which is not realistic at all but what ended up happening is when they cut off food from the government people had to go back into oppressive contracts with the landowners that they had been freed from just to be able to eat. Right. And then we see new systems where there's not even this kind of care or thought to how much people need to eat or any nutrition and a period where, you know, people are working convict leasing, you know, being arrested for fake crimes and then sent to work, but not being given enough food and a lot of death then too, just from poor nutrition or starvation.

[15:08] Where were you where were you going to do most of your research like how did you do that yeah I did uh I mean a lot of reading it's just a lot of um books and like oral histories transcribed, articles just you know the nose in the book and the computer yeah yeah uh I mean, how did it make you feel? And how did it resonate in your soul as what I would imagine is a very empathetic, compassionate human being, just reading and listening to scores of all of this? Yeah, I mean, it is. It's devastating, of course. Um but it's also a lot of the history i was writing is not my history you know um and i think, that that i don't know that's sort of two sides of a coin like on the one hand it's like hard to stories that aren't from your own background or descendants but there's also maybe some distance, from it you know um.

[16:35] I don't know. I just feel like it's necessary to bring this up to the surface. And so that's motivating for me. And it's all just so fascinating and something that people don't think about and talk about a lot. And so, you know, I always tell my students, if you're going to write, it has to be something you're really, really passionate about, or you're just not going to be driven to complete work. And this uh really i'm passionate about these topics and so that helps.

[17:12] So you you mentioned that they were kind of getting the you know the scraps they were given just enough food so that they could do their work but kind of maybe not have enough energy to you know rebel to start a revolution do you can you give me and the audience an idea of like what what were the primary foods that they were fed in this period um cornmeal is a big one and then um so that would be like the sort of base food um and then little bits of meat um.

[17:56] It depended on where, because some people could grow food, you know? Yeah. And sometimes enslavers thought that was good for themselves, right? Because then, you know, they didn't have to take care of that part of the feeding. And also, it gave people a little bit of joy and independence. And, you know, just enslavers thought they would be grateful for that. And then, you know, again, like thinking, oh, hope people don't turn on me or, you know, try to be free. So, you know, so sometimes there was this supplemental food. Yeah.

[18:46] Do you know what were the primary kind of health issues that people got back then? Yeah. So I have a kind of list in the book and it's interesting because these are nutritional diseases and like conditions that we mostly don't see anymore, except for like in some parts of the world where people have a lot of problems accessing nutritious food.

[19:16] But things like beriberi or it's like not coming to the top of my mind right now. They kind of like quashacor and like all these these diseases that I had to learn because I didn't know about them. But also like rickets and scurvy and and things that we still know you can get if you're deprived of a lot of minerals and vitamins. Yeah. Well, kwashiachor, that's basically, you know, being protein deficient. So that's interesting, which is probably a great sign that they were not getting enough calories. Yeah. Yeah, definitely. And then it's also interesting because instead of acknowledging that these were nutrition related diseases, the enslavers basically had their physicians diagnosed to say, oh, this is a biological disease. Race difference you know this is just a weakness in african people that that we white people don't have which is you know.

[20:23] A sort of biological racism that is still with us today yeah yeah yeah all right let's let's move to uh the chapter called americanization through homemaking okay um which you know to me is it's fascinating how it seemed that that that the i guess government and food policies were trying to Americanize and even erase cultural identities, whether you were Latino or Black or whatever. And so how did the government try and change the food traditions of immigrants and Native people? Yeah, well, it's really interesting. I do kind of a case study in there of California and a women's movement to target women and girls who were Mexican as the kind of homemakers and the core of the home and thinking that if they train them to eat like white Americans, then that would transform their households. It would stop, you know, the fathers and husbands from being criminals or, you know, not being patriotic, that this was the key.

Americanization Through Homemaking

[21:53] So they ran through all these lessons on, you know, what you should eat and when you should eat it. And they would have girls, you know, setting tables and this is very domestic, sort of well-meaning, you know, but very racist training. And the books are just hilarious to read through now.

[22:17] Yeah. Yeah. But, uh, give me, give me, give me another example of, of how these lessons, like how things, how, how basically we were trying to erase some of these, like, you know, cultural, uh.

[22:35] Indigenous cuisines, like, you know, Mexican for example.

[22:39] Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Um, yeah. So on the one hand, you know, just, well, you know, Mexican food, everybody loves it, but it's got a bad name. It's unhealthy, right? So we actually have these foods that are very healthy and especially in their, you know, indigenous forms. And, you know, people weren't eating just like bread made of white flour as we eat now, right? Everything that went into bread was highly nutritious, you know, but unrecognizable to ours. And one of the main sort of ingredients or foods is milk and cheese and so a lot of diets indigenous diets mexican diets that actually didn't eat the kind of cheese in the quantity that we have right and we have a condition called lactose intolerance right where a lot of people do not digest milk after their children and yet the united states has given i guess i'm kind of jumping ahead here but that's okay yeah uh but it's yeah you're jumping into the unbearable whiteness of milk i am i am but it's also it's also an answer to this all the chapters kind of overlap right yeah so there's like a big push to make people eat you know drink milk eat cheese um in ways that make them sick in a lot of different ways.

[24:07] But also to Americanize.

The Unbearable Whiteness of Milk

[24:11] Yeah. Well, and so speaking of, speaking of milk, well, actually I, before we go on to milk too much, I want to talk about like, if, when I think of like, I have traveled to central Mexico and I have visited with the Tarahumara Indians and I, They have something and you talk about it in the book called the three sisters. Yeah. Right. You have the corn, you have the beans and you have the squash. And there it's a very, very wonderful symbiotic relationship. And this to me is some of the most healthy food on the planet.

[24:51] And you go to Taco Bell now and it's not really the three sisters. No. I don't think any of this. well you know one ground up sister but yeah yeah exactly yeah exactly yeah yeah um so it yeah it is crazy how it you know some of these um healthy indigenous diets have been so just bastardized and um yeah and all the nutrition sucked out of it so you have perfect food and then And also this, you know, strange world where people are calling that food unhealthy, right? So we have, you know, like these programs, like the WIC program, where they're trying to give nutritious food to women, children and infants, right? But then the way they got this program going was kind of people sitting around saying, well, if we don't give them food, they're just going to serve their kids tortillas and beans. Right. Like that's terrible. And actually, it's incredibly nutritious. Right. So it's these kind of like racist views of what it should be a stapled food. But the staple foods are all very unhealthy, as opposed to in cultures where the staple foods are very healthy.

[26:18] Yeah, it's incredible that you bring that up. It reminds me, for years, I would go to Big Bend National Park, cross the Rio Grande River, and then go into the mountains on the Mexican side of Big Bend. And I became friends with a goat herder named Felipe. And he would let me kind of camp out at his little Pueblo. And I'm not exaggerating when I say he had a little stove that was made out of an old drum and what he would have, what he would eat for breakfast, lunch, and dinner was corn tortillas.

[26:55] With basically refried beans that he made himself. And that's it. That is literally it, unless he got some fruit from some people that dropped by. So you're right. And this guy was in his early 70s and fit as a fiddle and amazing. You don't even have to be up in the mountains. I actually spent some time living with a family in Veracruz in the mountainous regions. And it was the same. It was like, there's one pot of beans and you're making fresh tortillas and everybody gathers and that's what everybody eats every day. But I never want anything else. I was like, I actually very happily could eat this. It's completely satisfying, you know? Completely. Yeah. Completely. Yeah. Yeah. No, Dan Buettner would be happy to hear that too.

[27:46] All right. Let's go back to, you brought up the milk and how many people, well, you didn't actually say how many. Can you give me an idea of the percentages by race of what lactose intolerance people suffer? Here's a very broad thing. It's basically, if you're white, Scandinavian, Northern European, you're pretty solid to digest milk. And if you're anybody else, you're going to have problems, right? Not everybody, but like 80 to 90% of the population. Yeah. So it's highly skewed.

[28:28] And so do you know like when and why did this become such an important crux of the american diet oh yeah uh milk yeah yeah well so i guess people have been drinking it for a long time but they were getting really sick from it right so in the late 1800s early 1900s uh people were trying to drink this kind of unpasteurized milk, sending it from rural areas into cities to give to kids. Kids were dying at huge numbers because it was, right? And then milk was also passing on like tuberculosis and hand, foot and mouth disease. And it was a mess, right? But instead of just saying, okay, we're not doing this, let's pivot in another direction. We got a lot of promotion and propaganda about milk. Right. So there's this one guy, Evie McCollum. He was a nutritional biologist and he became this huge booster for milk.

[29:36] And Hoover, who was the secretary of agriculture, whatever, nutrition at that time, sent him around the country to make speeches about how great milk was. And his selling points were, Aryans drink milk. These are the people of the highest intellect and the arts. And so we should drink it, too. Right. There were so many. Strong clients. There we go. So, you know, they would go to schools, they would have little fairs around milk, they try to make milk fun.

[30:13] At the same time, we have the government trying to support the dairy industry, right, when we get into the 30s, and it's very depressed, and everything is depressed. That's one of the industries that gets a lot of support from the government, which leads to a lot of extra milk. And so that starts being given into school lunches, into, you know, kind of like food, emergency food, what we would call now, sent overseas. Right. So we've always had this supply and demand problem where the government's trying to make sure we have a huge supply supporting the industry, but people don't want it. And so it gets given to groups that can't say no. So, for example, going back to our first chapter, you know, indigenous people living on reservations, they get boxes from the government called commods because they're these commodity surpluses. Right. And they get massive blocks of cheese. And then we see also the government going around to poor black and brown neighborhoods, giving out huge blocks of cheese. This is because they've converted all this extra milk that they had to buy because consumers didn't buy into cheese to store it, put it all over the United States.

[31:40] Filled caves with extra cheese still couldn't figure out what to do with it said maybe we should just dump it in the ocean but then just started giving it to poor people.

[31:52] So we have this unwanted food that's also a symbol of whiteness and americanness that is being pushed around given to people who need it but who get sick from it.

[32:09] And it is now my understanding is it's the number one source of saturated fat in the American diet that makes sense because because it is it is put on and under and over and through just about everything uh and uh it's crazy it's like how many of these influencers now are pushing milk they're pushing cheese, they're pushing a lot of foods that, you know, I think that the science truly shows we'd be better off without. And, and I would imagine, you know, these people.

[32:46] Most demographics that, um, have a lactose intolerance. I mean, cheese is basically just a, it's a, it's a concentrated source of milk calories. Yeah. Right. Yeah. I mean, it's not like, like in just as, as an example for listeners, like a glass of whole milk is about 150 calories. If you were to take, you know, uh, a little block of cheddar cheese and turn that into eight ounces. So eight ounces of milk 150 calories eight ounces of melted cheddar cheese 960 calories so it's almost six and a half seven times the amount of calories you know you can see why it's good for people who are hungry like it's not the kind of thing you can turn down because it is like so full of calories, but I mean, not. Yeah. Yeah. Well, yeah.

[33:43] And, and I think you mentioned too, how, you know, milk, milk has been, milk consumption has been going down as of late. Yes. Oh, I mean, not even just as of late, I would say over like 40 years now. So I used to say 30 but i think i started saying that about 10 years ago so yeah it's uh it's been on a very steep and steady decline especially now well i think people don't feel good when they drink milk so they don't want it and now we've developed so many great alternatives that you really don't need even if you crave you know whatever it is that is part of milk you can get the same thing from a different product that's not going to make you sick.

[34:33] In your research, what are some of the, side effects from lactose intolerant that people experience? I think, you know, it's not a lot of my research. I mean, lactose intolerance, I think, you know, you'll get sick, you'll feel uncomfortable. It's unpleasant. But there's also a lot of research that is connecting milk consumption to more serious health conditions. You know, and so like studies coming out of Harvard and other really respected places that it's also, you know, contributing to heart disease, cancer incidents, at least higher risk of these, things, strokes, you know, that is even more of a problem. Because when we think about lactose intolerance, it's like, it's bad. But a lot of people can say, well, I'll choose that, you know, Cause that's, I can put up with it, um, you know, or I'll take a lactate or whatever. Right. But then when it comes to these other things, I don't think people are making choices cause they either don't know or they're, you know, it's just not laid out in that very clear way because the reactions are not immediate.

[35:54] Lactose intolerance is like, I drank it. I felt sick. And then I, I made a cost benefit analysis, whether I want to do that or not. Right. But other connections to more serious types of health issues, you don't make a choice each time you're consuming. Right. And so to me, that's kind of more insidious. Yeah. I don't know how old you are, but I am when I was in the 25. Go ahead. Okay. Yeah.

[36:29] Wonderful. Yeah. So I was born in 63. And so I can remember in the late 60s, early 70s, at lunch, we would always each be given a little carton of milk. And...

[36:45] Never even thought anything of it. Right. Just kind of drank it down thinking that it was it was good for you. And I just think how how egregious that was that they were making us, for the most part, drink milk. Right. Well, if you didn't want to. Yeah. No, I'm going to say like it hasn't really

School Food Failures

[37:04] changed is what I think is is odd. Because so my kids went to school in Waikiki Elementary, it's called in Hawaii anyway. And so like there, they also gave out the little things of milk and the kids couldn't even leave the cafeteria if they didn't drink it. I mean, mine are vegan and they didn't, but generally it's like, you could throw all your food in the garbage, but if you didn't drink your milk, you had to stay in the cafeteria. So think of how many years in between that is. And we still have that. Yeah. So if yours so i was i was going to ask you this and this is i think a great time what is your personal food philosophy are you are you vegan i am i'm even wearing my one of my vegan shirts for you here but you can't really see it how long have you been vegan um quite a long time many many, many years. Yeah. Well, high five, virtual high five.

[38:11] And did your children, did they need a note saying that, you know, they were vegan and that they were, they didn't have to drink the milk? Yeah. I mean, so that is required, but you know, the school wasn't that strict on it because they kind of like from entry, entry it was known it was well known all right those kids were not going to be drinking the milk but um.

[38:37] They were the only ones. Wow. Well, because I mean, were a lot of the students Hawaiian? Yeah. All kinds of, you know, there's a lot of mixed race identification. I'm just wondering if Hawaiians fall into that, you know, that population that do have a kind of an inherent lactose intolerant for the most part. Yeah. Yeah. Hmm. Wow. Let's go into the school food failure. And you know in this chapter you yeah well yeah yes but but you know you know you you you talk about how the school lunch programs are used as a dumping ground for all these agricultural surpluses you know going back to the great depression um so what what else besides milk Oh, yeah. So basically, you know, corn is one of these foods that gets subsidies.

[39:37] But then because there's so much of it, it doesn't look like, oh, well, here's a nice ear of corn for you, right? It's actually being processed into mostly corn syrup, which is what would show up in a school meal, right? Same with soy. Again, it's not like you're going to have like some edamame soybeans or something. No, you're going to have oil, right? It's converted into oil. And so in meat and milk, what you see is that you get a lot of processed food because that's the kind of most cost effective way of transforming these surpluses of these subsidized commodities into something for mass consumption.

[40:24] So it's like, you know, here's your tater tots, here's your chicken nuggets, you know, the pizza, all of the kind of junk food. Yeah. And of course, it's a double whammy because not only is it, you know, feeding insulin resistance and obesity and the beginnings of heart disease and other chronic disease, these kids are also, it's training their palate to really like these hyper-palatized foods. Yeah, that's why we've seen a lot of entry of like the fast food industry into schools over the past few decades. Right. And they are very hyper aware of that and really trying to get in so that that's what that's going to be your comfort food, even when you're an adult.

[41:16] Right. that you like you said you're developing a palate and in addition to what you're saying about you know the sort of long-term health consequences there's also just the daily so you know we all know like if we choose we're going to eat some kind of fast food or highly processed or like deep fried i'm sure you never do that but if you did then uh you know you're just not going to feel good. And so you're like, okay, I'm just not going to feel good for a few hours. I'm okay with that. But when you're a kid in school and that's what you're having for breakfast and that's what you're having for lunch, it's pretty hard to then like sit through the day and be receptive to learning and it just affects everything, right? So not only your health and nutrition, but even your education, which then of course leads to like opportunities in life, right? So it's pretty significant. And, you know, just, you mentioned the, um, the title of the chapter about survival pending revolution. And that was a reference to the black Panthers breakfast program.

[42:27] So I think this is a good time to bring that up because they recognize how important that feeding school children is. Right. And if they would start the day with nutritious food and also in community, you know, and there's that cultural element as well, that they were going to have more successful kids. Right. Which is a successful community, a successful world for all of us. Right. And so the programs that we have now that the government sponsors, a lot were inspired by the Black Panthers, except they weren't keeping the kids' well-being in mind. They were keeping in mind the well-being of the agricultural and food industries and their need to get rid of these subsidized commodities and then feed them to kids, kind of killing two birds with one stone, but then maybe a little too much on the killing side.

[43:27] Tell me why? Is it just because the milk and the corn and the soy lobbyists are just so... Intertwined with, you know, the government? I mean, why are we not subsidizing fruits and vegetables and whole grains? Why are we subsidizing, just to put it bluntly, all the crap? Yeah, great question.

[43:54] So this all kind of had its start back in the 30s when the selection of which foods to subsidize was somewhat correlated to the needs of the country, which was people were hungry. Right and so as you know you've said like with cheese or other kinds of these foods these kind of foods do make you feel full right the problem is that once that problem was basically solved we had new nutritional problems which was this kind of junk food and all the things that we've mentioned that would be solved by eating more fruits and vegetables and beans and other things that you know whole grain whatever that are healthy but are not subsidized but at that point because of the extent of subsidies that were given over the first few decades of the program those industries became so rich they consolidated you know they just took over and then they became highly influential over policy so even if at this point the government and out of like interest of the people wanted to pivot to put more money into those types of crops the resistance is too strong so the government kind of

Food Policy and Race

[45:16] lost control over its own food policy and does now cater to the strong lobby movements.

[45:24] You know, to the sort of overlap between these big industries.

[45:29] And positions in the administration. And they're so entrenched, it's been impossible to make that change. Hmm. You know, there's a, I can't remember which country it is. It's either Finland or Norway. Okay.

[45:46] Where they had one of the highest rates of heart disease in the world, like comparable to the United States, if not a little bit higher. And they basically did an about face and they started subsidizing fruits and vegetables and berries and things like that. And I'm wondering if you if you came across this in your research and literally turned it around overnight, the amount of heart disease, obesity, all these things. And they just got their act together. I mean, Winston Churchill a long time ago said that the greatest asset that any country can have are healthy citizens. And I don't know what it's going to take for us to start investing in our children, in the school lunch programs.

[46:40] And, you know, subsidizing the right foods and everything else that's, you know, doing the right thing. Yeah, I think it takes a different kind of political framework, you know, that is not so heavily leaning into the capitalist side of, you know.

[47:01] Because a lot of other countries and, you know, the ones you mentioned or Canada or, you know, just a lot of different countries, They're still capitalists, but they're, they're sort of tempered, you know, they're like democratic socialists or, you know, they're, they just have more of the socialist philosophy, which wants to take care of citizens. Right. But when you're heavy capitalists and you're very focused on money-making and corporations, then that's built into the idea of the system that you're just going to sacrifice some people. Right. And so it's profits over people and that's what we're living under. And so I think where you can see more of that philosophy that you're longing for is maybe on a state or local level where there's more incentive to like take care of your citizens. And it's closer, the government is closer to the people and more invested in like satisfying its constituents or, you know, being successful. So where we might not see changes on the larger federal level anytime soon, we can see them in the sort of just more local, you know. Yeah.

[48:24] You know, it's interesting to me because...

[48:31] I look around and it seems more and more that, at least from my very narrow vantage point, that all of America is becoming more and more unhealthy. You know, the amount of obesity, diabetes, everything. And to me, you know, I think this dovetails nicely into, you know, your chapter on delicious and how there's just, you know, there's racist food marketing, but I also see it as just marketing in general, the Doritos and the Coke and, you know, all the hype, the ultra processed food that people, it doesn't matter if you're white, brown, black, green, blue, you as a human being, your palate is drawn to these foods. You know, Doug Lyle, who I've had in the podcast several times, has co-authored a book with Dr. Alan Goldhammer called The Pleasure Trap and how you're eating these foods and everything about them feels so right, but they are so wrong as far as what they're doing to us health-wise. But I'm getting off. So explain how food marketing is in fact racist. Yeah.

[49:50] Well, we have certain ideas in society about who eats what, right? And these are reflected, created, reinforced by marketing, right? So you'll see if it's going to be a health food, it's going to be yogurt or something, then you're going to see these like white, thin people, right? But if it's going to be like McDonald's, then you're going to see this very race-targeted marketing, right? They have websites that are identity-based, you know.

[50:30] They sponsor community events, right? They really want to have people identify with fast food, but also for everyone to believe that there are certain populations. And this goes back to even what we were talking about, the Mexican immigrants and the attempts to Americanize. Part of the battles against their food is this idea that it's unhealthy. People are lazy. They're ignorant. They don't understand nutrition. And their food is bad right so um they should change right yeah yeah so we just we see all these images and we internalize them even when they're alive no i mean if you think about like the vegan movements and you see like a lot of white facing thinking about being vegan right in fact like there's a very large percentage of black population that is vegan but that's you know it's just not as a popular an image right.

[51:47] Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. No, I I think it was I heard five years ago that the fastest growing population of vegans were in flat, in fact, black Americans. So, I mean, bravo.

[52:02] So do you think that I mean, how much agency in 2025 do some of these different demographics have? I think for all of us, we're very circumscribed by, you know, what is around us.

[52:20] We want, of course, we all want to feel agency, right? And this is a really kind of a rallying cry in the United States, especially the freedom, right? And so it's even like freedom in food to choose what you want, even if you want to choose a horrible chemical that's like going to ruin the lining of your internal organs, right? It's like, no, we can't ban those things because we must be free. But everybody is constrained by their external circumstances. So like how much money do you have? How much time do you have? How close do you live to a place that is going to sell you the food you need? How much is it going to cost? Right. How many jobs are you working? How many people are you caring for? How many people do you have to feed on what budget? Yeah. So, you know, what can you walk down the street and get versus you need to go to another neighborhood? Do you have a car? What is the bus route? You know, all of that. So all of these things actually define what we eat.

[53:23] And if we have a lot of privilege, then, you know, maybe we're wandering the aisles of Whole Foods and like checking ingredients and saying, oh, I don't want that or I do want that. But most people are just, you know, working with a budget, working with time constraints and working with whatever's closest to make it all work for the number of people they need to feed, even if that is just yourself. Yeah what's your what are your thoughts on food deserts.

[53:56] Well uh unfortunate right uh we do have this system of you know food apartheid in in the united states where some there's a concentration of good food in some places and really crabby food and others and um you know that should change and i would love to see the usda use some of its money to just open up, you know, sources of food and in neighborhoods where you can't get it, make it cheap, make it accessible. You know, I think that should be part of the program and we should get away from the idea that, well, people are just making choices. They're not, you know, they're not just inclined towards unhealthy food and this whole characterization of certain foods as of certain cultures mean unhealthy.

[54:50] I think everybody basically wants the same things. And even if it's your pleasure trap foods. Yeah. You still want it probably in moderation, right? Because our bodies also are telling us like when we eat stuff that's really healthy, that feels good. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Your last chapter, what's law got to do with it? Mm-hmm. And it kind of connects all the previous chapters, but emphasizes kind of the.

[55:22] Manipulation and control of food and how it's been kind of embedded in American law and policy. And this is not just a historical accident. So I'd love for you to kind of, Expand on that. Sure. So an argument that I'm making in that chapter is that these foods laws and policies that control, you know, what gets subsidized and who gets to eat what are actually unconstitutional. So they're not just bad laws and policies. They're like next level. Right. And so part of that, I'm thinking about these amendments to the Constitution that came up after, you know, in the reconstruction period after emancipation and how, first of all, we're supposed to have equal protection of the law for everybody. Right. And so if our food laws and policies favor people because of their race, then that is not allowed under the 14th Amendment.

[56:37] And then under the 13th Amendment, which did abolish enslaving people and voluntary servitude, also says the court has said that means any kind of vestiges of slavery, like anything that happened during that period to facilitate enslaving people and has continued in our society since then, violates the 13th Amendment. And that is what we see with food law and policy. The law upheld that.

[57:12] Total control of the food that enslaved people could eat. And then throughout history has enforced different kinds of systems that were the same. So even just saying, well, you can't, you know, you can't hunt or fish on certain days where sharecroppers had to work, you know, we're off so like making it impossible right and we've just had a system that has never changed in that regard it's it's been a through line of history and so i'm arguing there that the 13th amendment also means that we can't sustain these food laws and policies that create and perpetuate these racial disparities because they violate the constitution is anybody else uh bringing that to uh uh you know the right the right people's attention uh we'll see i know that um there were there was a suit from some of the animal legal defense fund people working on milk in public schools that they were using some of this scholarship of mine.

[58:33] So, you know, trying to get it to the,

Law and Food Inequality

[58:37] ears that want to listen and make change. Yeah. Yeah. Well, as we've talked about, I mean, this is, to me, this is one of the most important things I think that we could focus on as a, as a culture right now. It's just, yeah. I mean, truly. I think it was, it was really helpful to win a couple of awards with this book. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. No, I saw you, You won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize winner. What else? Anything else I should know about? Yeah, the James Beard Award. Oh, my God. Well, that's a little lesser known one. Yeah, exactly.

[59:18] Wow. Way to be. Way to be. Because that really brought it to a new audience, right? Yeah, it sure did. Yeah. Golly. I mean, and you got a really nice blurb from Michael Moss. Who has appeared at one of my events and wrote, what, Sugar, Fat, and Salt, right? And a couple others. I mean, yeah. So, I mean, how perfect. Now, you've done really a remarkable job stringing it all together here. And it really is, for somebody that wants to know the history of our food in this country, and those that I think have been marginalized because of it. This is a must read. Absolutely. There she blows right there. Ruin their crops on the ground. What are you having?

[1:00:12] So it's a couple hours behind there. What are you having for lunch today? Have you figured it out? Okay, great question.

[1:00:22] Well, okay, maybe not a great answer, But I've been on this kick of making about once a week. It's a cheesecake. It's a banana chocolate cheesecake. And that's the one. That's the one. Well, you know, that's the next thing I'm going to eat today. Got it. Got it. And is this a homemade recipe? It comes out of Issa Chandromoskowitz's. Oh, yeah. Yeah. It's in her pie book. Oh, gosh. Yeah. Well, she's quite the chef. It's funny. When I was first writing my book, my first book, The Antitude Diet, she was, she was a real force. This is back in 2000, you know, 2008, 2009. Oh, she's been legendary forever. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. She's something else. Well, Andrea, where, where can people go to get the book and learn more about you and everything you're doing? Okay, great. I mean, the book, if you don't have it in your local bookstore, tell them to order it. Tell them it won a James Beard Award. They like that. Soon that sticker will be on the cover, too.

[1:01:45] But honestly, anywhere books are sold, you can get it. You can listen to it. There's an audiobook, too, if you prefer.

[1:01:52] Yeah. And so I always like to support the independent bookstores, but that's not an option for everybody. So by any way you can. And then you can Google me. My name will come up first on my name, which is pretty amazing because there's a lot of people with that name. There are. Yeah. But yeah. So I'm a law professor. Is this your first book, Andrea? This is my second book. Second book. Yes. But the first book came out of some research that I was doing actually for this book on milk.

[1:02:31] Because it is about breast milk. And breastfeeding. And so the first book, which is called Skimmed, tells a story of a group quadruplets, these sisters. They're called the Fultz sisters. And they were born in 1946 in North Carolina. They were the first recorded Black quadruplets to survive childbirth. And they had a white doctor who decided to name them all after his own family members. And then And he used these little babies to do experiments with vitamin C. And then he auctioned off the rights to use them in promotional materials to formula companies. So they became the first black formula models.

[1:03:23] And so that. Yeah. Where were the parents doing all this? Well, so the parents, so the father was a tenant farmer on a tobacco farm. And the mother, who also had six other kids, she could not speak or hear. And so basically, this doctor just kind of took over. And then when the girls turned six, he had them, he went to a judge and he had them taken away from their parents. and a nurse that worked for that doctor became their guardian.

[1:04:04] And so they moved off the farm. I mean, it's an incredible story. Do you know if they're still alive today? They're not still alive. No, because, yeah. Another part of the story. So basically, they became these pet milk formula models. And they were barely paid. They lived in poverty their whole lives and made a lot of money for pet milk. But they had a kind of supply of this evaporated milk, which is what formula was at the time, until they were 18. They drank a lot of that. They all got breast cancer, which is highly unusual for multiples, right? And so three of them died very early. And then one of them survived until a few years ago. Oh, my God. Yeah. But there's like, if you read the book, it's got a lot of like fascinating history of them. Yeah.

[1:05:00] You know, just the heinous things that we as humans have done to other humans is it's very unsettling and disturbing. But I'd like to think that there's many more, you know, compassionate, empathetic, wonderful people out there than that that are doing good and doing the right thing. So thank you for, you know, exposing and bringing all this to light, Andrea. Wonderful work. Thank you. And I appreciate you very much. I appreciate you. I appreciate you, the work you do, and for having me come and talk to you and everything you're saying. Yeah. So can you give me a virtual Plan Strong fist bump on the way out? Here we go. Boom. All right. See you, Andrea. Okay, bye.

Conclusion and Reflections

[1:05:56] Andrea really opened my eyes to how deeply food, history, and inequality are all intertwined. Her work reminds all of us that the fight for food justice, it isn't just about what's on our plates. It's about who has access, who benefits, and how we can all be part of a more equitable system. And as you and I both know, this discussion is far from being settled. Ruin Their Crops on the Ground is available now, and I'll be sure to put a link in today's show notes. I want to thank you all for tuning in to this important conversation, and a huge thanks to Andrea for sharing her knowledge and passion with all of us. Let's remember, eating well is important, but understanding the systems behind our food is just as crucial. Until next week, thanks so much for listening, and always, always keep it Plant Strong.